HARRY POTTER'S CURSED RETURNS

A long-running play that's short on profits.

EXCLUSIVE: As the crush of fans mobbing the Lyric Theatre stage door attests, Harry Potter movie star Tom Felton has re-energized Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. Nearly eight years after the wizard drama began previews and set a weekly sales record for a Broadway play, it’s outselling every current show, including musicals.

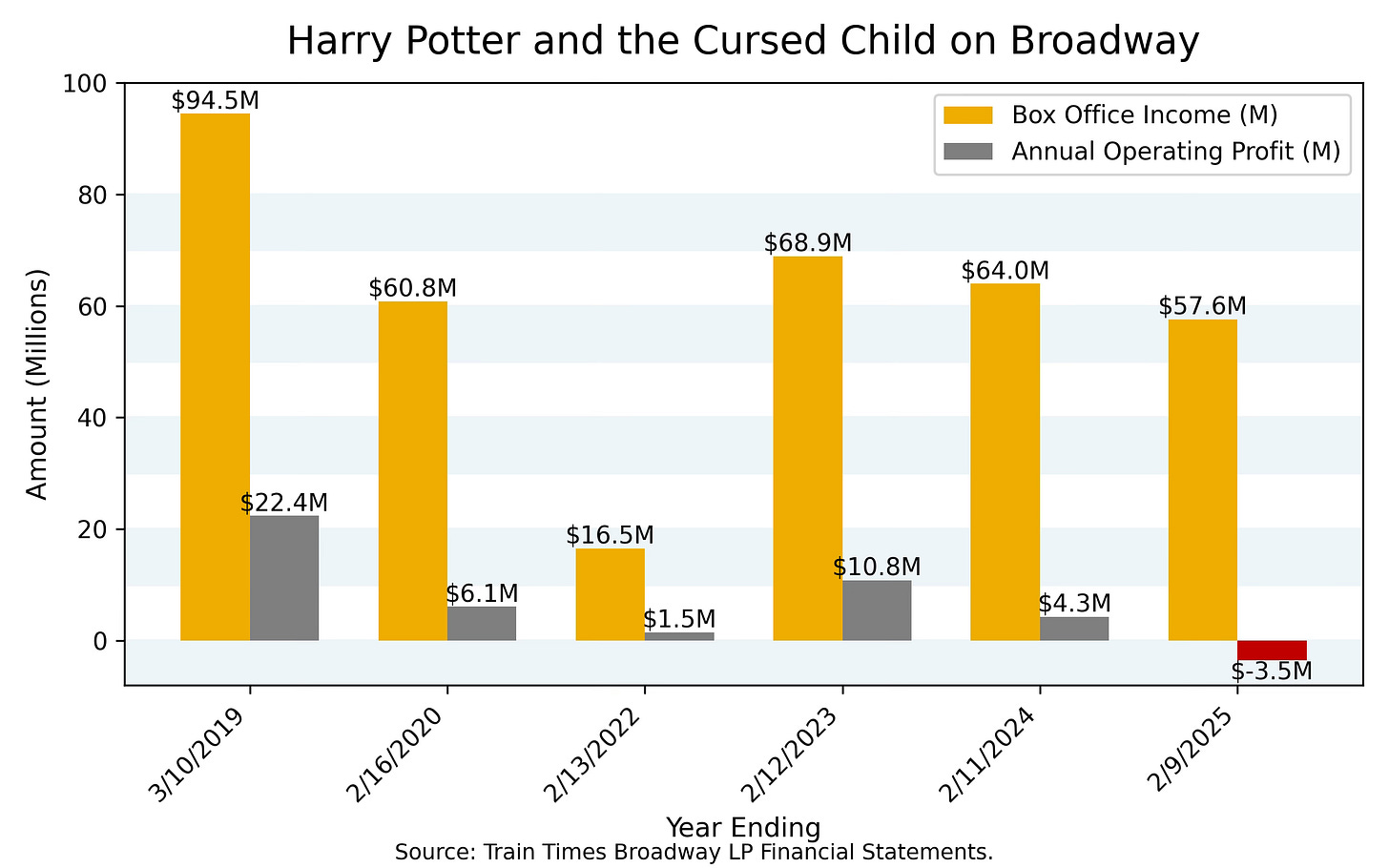

For investors, however, the Broadway production has been less magical. To-date, they’ve earned a total return — after recouping their initial stakes — of just 6%, rising to 11% when including the benefit of a state tax credit to encourage theater production. Money market funds have been more lucrative over the same period.

The Broadway production posted a $3.5 million operating loss in the year ending in February 2025, with additional losses in subsequent months. The lead producers warned investors not to expect another profit distribution anytime soon. Those same producers have earned millions of dollars in royalties and other revenue tied to the New York run, in addition to their share of the modest profits.

Broadway Journal obtained results for Train Times Broadway L.P., the entity that produces the acclaimed spectacle, via freedom of information requests from New York Attorney General Letitia James. In addition, the AG’s office provided records for Train Times SF L.P. -- which mounted a run in San Francisco that proved to be short-lived. I also reviewed financial statements filed by Cursed Child companies in a U.K. government registry, along with internal production communications.

Despite grossing $456 million in New York, Cursed Child is a textbook case of a show that takes years to earn back its investment — if it’s fortunate — and then struggles to sustain momentum. The Broadway transfer of the West End hit was budgeted like a musical and an expensive one at that, with a large cast (currently 38), spectacular effects and a venue lavishly renovated by the production and its landlord, the multinational theater company ATG Entertainment.

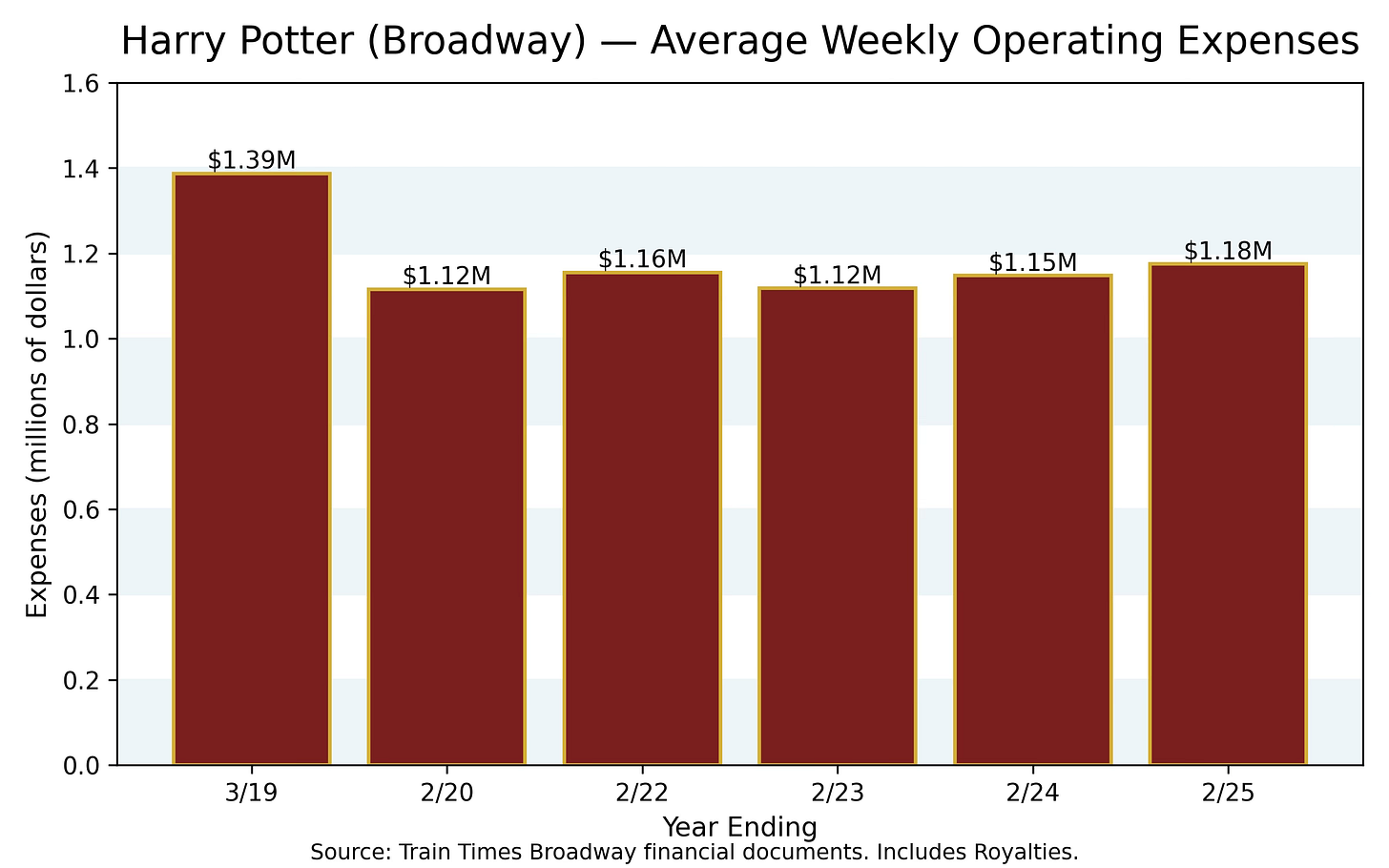

Capitalized at $35.5 million, with weekly operating expenses exceeding $1 million, Cursed Child is produced by Sonia Friedman Productions — which is owned by ATG — Colin Callender and Harry Potter Theatrical Productions, which represents the interests of Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling.

“Our producers are proud of how we’ve been able to pivot and respond to the ever-increasing costs of producing theatre on Broadway, while still allowing new generations to attend,” production spokesman Adrian Bryan-Brown said in an emailed statement to Broadway Journal. Bryan-Brown added that “during a particularly challenging time for live theater everywhere, especially Broadway, we have delivered returns in three major markets” -- London, New York and Melbourne.

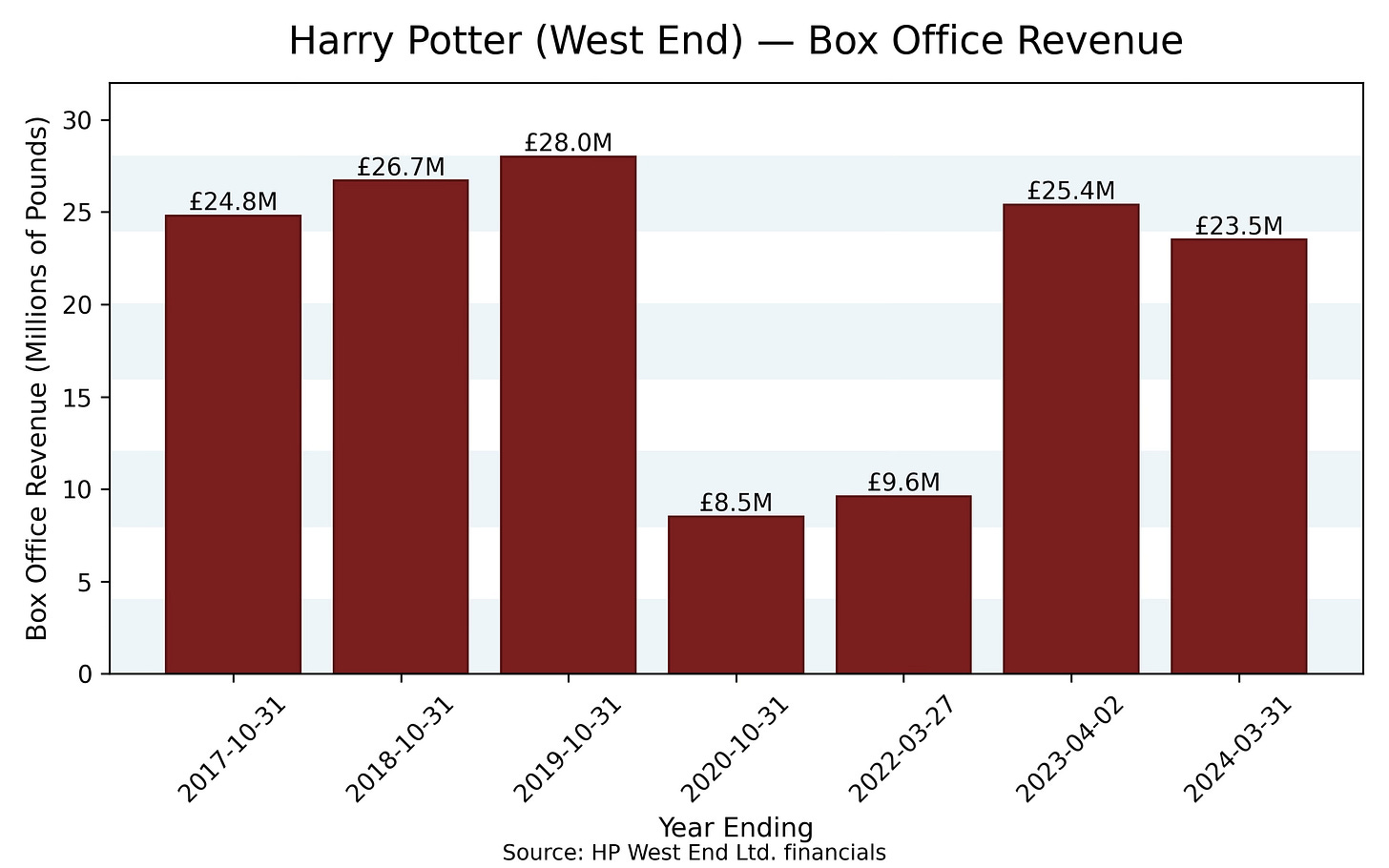

Cursed Child has delivered its best investment returns in London, though rising running costs have ushered in recent operating losses. Producers privately cited higher salaries for cast and backstage staff, the cost of maintaining an aging production, and a nearly 20% drop in summer sales for long-running shows.

Cursed Child in Melbourne ran five years but generated an investor profit of just 0.5%. A San Francisco production, which had a pandemic-interrupted run ending in September 2022, lost 76 percent of its $33 million capitalization as of year-end 2023. A Toronto production ran just over a year at a loss.

In Washington, D.C., President Trump’s August deployment of the National Guard hurt Cursed Child’s engagement at the National Theatre this summer. The producers told investors that audiences stayed home and tourism collapsed, leading to losses that will delay recoupment.

In 2013, Rowling needed coaxing to extend the Potter brand, which comprises about 600 million copies of books sold, plus movies, television, video games and theme park attractions. “For years I’d turned down proposals to adapt the books for the stage, but this was something different, something new,” Rowling wrote in a Cursed Child coffee table tome. She co-wrote a new story focusing on Harry’s middle son, which became the basis of the play by Jack Thorne. The London production played to full capacity in its early years and won a record nine Olivier Awards.

As is typical of an offering licensed from a U.K. juggernaut, Broadway investors accepted tough terms. For example, the underlying rights owner (Rowling) and the West End company (owned by Rowling and others) and affiliates command 31 percent of net profits. The Book of Mormon, which arrived on Broadway without a prior run and wasn’t based on a book or movie, allocates just 4 percent of net profits to insiders, which is known as net profit participation.

When Cursed Child opened in New York in April 2018, Ben Brantley in the New York Times called it “enthralling,” and Sara Holdren in New York magazine deemed it “extravagantly entertaining.” A rare, two-part Broadway play requiring two tickets, Cursed Child was a must-see in its first year. It earned $22 million in operating profit on $95 million of box office income. By July 2019, it had returned 60 percent of investors’ capital.

But in the year ending February 2020, grosses for the Broadway run plunged by more than a third. Producers played down the slump, telling the New York Times’ Michael Paulson that “we have now settled into a viable business-as-usual weekly sales pattern, if ‘business as usual’ is ever something that’s possible to say in the theater.”

Behind the scenes, the producers took steps to hasten recoupment. They waived their fees and office charges when weekly grosses fell below a certain threshold. Royalty participants, including producers, deferred some income until the show recouped and earned a small profit. The producers and an undisclosed investor -- possibly ATG -- delayed repayment of $9.9 million owed to them until the production built up reserves.

The show resumed performances at the end of 2021 following the Covid-19 shutdown debuting a condensed, one-part version at effectively half the price. It retained what the Times’ Alexis Soloski called its “diamond-sharp” staging and “dazzling” visuals. Grosses rebounded in the year ending February 2023; and it repaid the $9.9 million loan to insiders and recouped its capitalization.

Business slumped again in 2023-24 and 24-25. Some Potter watchers speculate that Rowling alienated audiences with her comments about transgender issues. The show lost money even after producers shaved the running time for a second time, in November 2024, to reduce costs. The producers privately blamed a drop in tourism from Canada for part of the decline. They recently told investors that operating income from Felton’s engagement — Nov. 11 to May 10, 2026 — will be used to offset losses and rebuild financial reserves, not to make profit distributions.

ATG Entertainment, which has a long-term lease on the Lyric, has collected more than $34 million in rent on Broadway from Cursed Child. In the year ending in February 2025, rent consumed nearly 11% of box office sales. To be sure, ATG has its own real estate expenses. In 2013, it paid $64 million for the lease to the Lyric, and later spent millions more on Cursed Child renovations.

The three Broadway producers have collectively earned more than $10 million from the show’s royalties, office charges, executive producer fees and their share of profits and the state tax credit. They also received some of the $4 million that the Broadway company paid to the West End “mother company” in royalties and net profit participation.

HPTP Holdings Ltd., which represents Rowling’s interests in the show across the U.S, U.K, Canada, Australia and other territories, had net assets of $17 million as of March 2024 (disclosed in pounds that I converted into dollars). A year earlier, it paid Rowling a $10 million dividend, following a $16 million dividend from another Rowling entity in 2018.

Investors in the Broadway show have shared just $2.3 million.

Inequitable rewards have been a persistent sore point for people who raise money and invest in shows. David Carpenter, who presented the scrappy and successful unauthorized Potter parody Puffs, said that the roles of producers and investors aren’t comparable.

“Being an investor isn’t a job on a show,” Carpenter said in a text. “The lead producers have to make 100 decisions a day that starts with them taking the risk and the idea to get the show produced. It’s years of work with no pay. When the show is running, the lead should get paid, as any CEO should for running a medium-sized company. The investors have lost sight of that.”

Carpenter added that the disconnect in earnings is the least of Broadway’s problems. “The industry is broken, dysfunctional and corrupt.”

Rising production costs, which have long bedeviled Broadway, accelerated during the pandemic. “People are asking what can be done,” said John Breglio, a producer and retired theatrical lawyer, in an interview. “Nobody has come up with a silver bullet.”

To catch Felton on Broadway reprising his role as Draco Malfoy, fans are paying up to $678 a ticket and waiting for hours outside the stage door for a chance to meet him. “It’s amazing to see someone we grew up with taking that role,” said Stella Racine, a 36-year-old waitress and bartender who flew in from Seattle.

The Broadway production has privately forecast sales of about $70 million for Felton’s six-month run. If it can sustain anything close to today’s frenzied business through 2026 and make substantial distributions to investors, the turnaround might merit a case study at Hogwarts Business School.

To reach Philip Boroff, feel free to email pboroff@bwayjournal.com.